A Push for Speed but at What Cost?

The government says it wants to make the courts more efficient by introducing judge-only verdicts in Magistrates’ Courts and creating new “Swift Courts.” While the goal is faster justice, the reforms have raised serious concerns about how far efficiency can be prioritised without weakening long-standing protections in the criminal justice system.

Justice Secretary David Lammy MP confirmed that jury trials will no longer be available for offences carrying a maximum sentence of under three years. Juries will remain only for indictable-only offences such as rape, murder, aggravated burglary and grievous bodily harm. All other cases will be diverted to judge-only courts, depriving the defendant of the right to a jury trial.

Under the reforms, magistrates will also gain complete discretion to decide whether a case should be sent to the Crown Court. Defendants charged with triable-either-way offences would lose their right to elect a jury trial, meaning their guilt or innocence would be determined by a single lay magistrate. The government intends to increase magistrates’ sentencing powers from 12 months to 18 months, potentially up to 2 years, allowing more serious cases to remain entirely in the lower courts.

The Case for Reform: Backlogs and Delays

Lammy, a former barrister, argues that judge-only trials will be “around a fifth faster” and help ease pressure on a Crown Court backlog nearing 80,000 cases, with projections suggesting it could reach 100,000 by 2029. He also pointed out that six in ten victims of rape withdraw their cases due to delays, a statistic the government believes these reforms could help improve.

For ministers, the changes are presented as a necessary intervention to prevent the justice system, already under strain, from sliding into crisis.

Concerns About Fairness, Transparency, and Representation

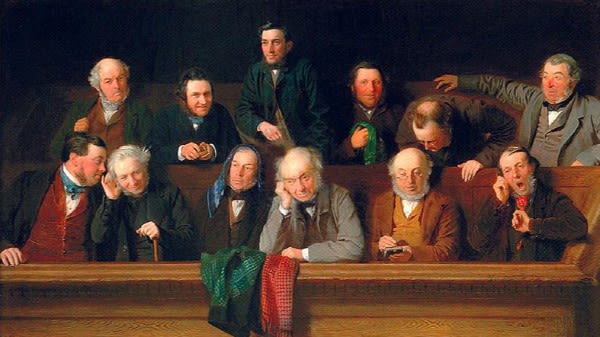

Critics accept that backlogs must be addressed but question whether removing juries is the right solution. Many warn that fairness and transparency could be weakened if verdicts increasingly rest with a single magistrate rather than a group of citizens.

Brett Dixon, vice president of the Law Society, cautioned that allowing “a single lay magistrate operating in an under-resourced system” to decide severe cases strips away essential safeguards. Campaigners also argue that public participation in criminal decision-making is a cornerstone of democratic justice. Abigail Ashford noted that reducing lay involvement risks “undemocratic decisions being made by judges,” especially in communities already distrustful of state institutions.

Some critics suggest the reforms could raise issues under Article 6 ECHR, which guarantees the right to a fair trial. Concerns about bias are amplified by the demographic profile of magistrates, who are disproportionately white, older and female. Studies suggest they are more conviction-minded than juries, raising fears that removing juries could widen existing inequalities, particularly for defendants from marginalised backgrounds.

Supporters of the reforms argue that neither Magna Carta nor Article 6 explicitly guarantees jury trials for all offences. Opponents respond that the rule of law is not simply a matter of written guarantees, but also of tradition, checks and balances and accountability, all of which weaken when lay participation is reduced.

Balancing Practicality and Principle

Some advocates of judge-only trials point to concerns about jurors accessing online information despite judicial warnings. Critics reply that judges also hold unconscious biases and make decisions without public transparency. Removing juries, they argue, does not solve the problem; it may simply hide it.

Ultimately, the reforms highlight a fundamental tension at the heart of criminal justice policy: the government is prioritising practicality and speed. At the same time, critics believe that core principles of fairness and community involvement are being compromised. Judge-only trials may ease delays, but many fear they could also undermine public trust, limit defendants’ rights, and deepen existing inequalities.

As opponents warn: efficiency may be gained, but legitimacy may be lost.